Dr Michael Joseph Way is a senior research scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and a part-time visiting professor at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Uppsala University in Sweden. His scientific interests include both the multiscale structure of the universe and the modelling of planetary atmospheres. In recent years, he has published several research papers on Venus and its climate history. In his second interview with OHB, he explains how the new Venus missions recently announced by NASA and ESA complement each other and what scientific findings can be expected from them.

It's been two years since we last spoke. Is your interest in Venus still going strong?

Dr Michael Way: Oh yes! I'm very involved in many Venus projects with different people around the world. In November there will be two big workshops, which I'm currently getting ready for. Unfortunately, they will both only happen virtually.

So you are still affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

We are, unfortunately, although just two weeks ago I was able to travel to Switzerland for a book workshop on Venus and I really enjoyed the opportunity to once again meet my fellow humans in a science setting.

Are you currently working on a research paper on Venus or is it just workshops?

Oh no! I'm working on several papers. That's the nature of the business.

What are they going to be about? Or is that still a secret?

Well, a part of them are for a book project with ISSI, the International Space Science Institute in Bern, Switzerland. And each of the chapters of the book will also be published as a separate paper in Space Science Reviews, so I'm a co-author on at least four papers that will come out of that. I think they will be extremely useful and interesting for the community given the upcoming new missions. And then there are a couple of others that I'm working on that I can't go into too much detail about, but that I'm also very excited about.

Speaking of the new missions: In the interview we did in 2019, you said we needed new missions, but did you anticipate that they would actually be selected for implementation as early as 2021?

I think it was a pleasant surprise for everyone that we are getting three missions. People would have been overjoyed with just one mission, so we are very excited that we are getting all three. And each mission brings something unique while they all also complement each other. It's going to blow our minds when we get this data from Venus.

Were you involved in defining the science case for the missions?

Not really, unfortunately. I'm not really a mission person, I'm a modeller. But they have used our models to define the goals of the missions. And of course one of the goals of all these missions is to determine whether Venus has ever had temperate or what we call habitable conditions.

What scientific insights are you hoping for?

From my modelling perspective, I'm very excited about the DAVINCI mission. That is because the DAVINCI mission is going to be an in-situ mission. Its instruments will be able to analyse noble gas isotopes and other constituents of the atmosphere including the deuterium-hydrogen ratio. That will give us a much better handle on the evolutionary history of the planet and also an idea of how much water the planet had, when it lost that water and ideally even the timescale of that loss.

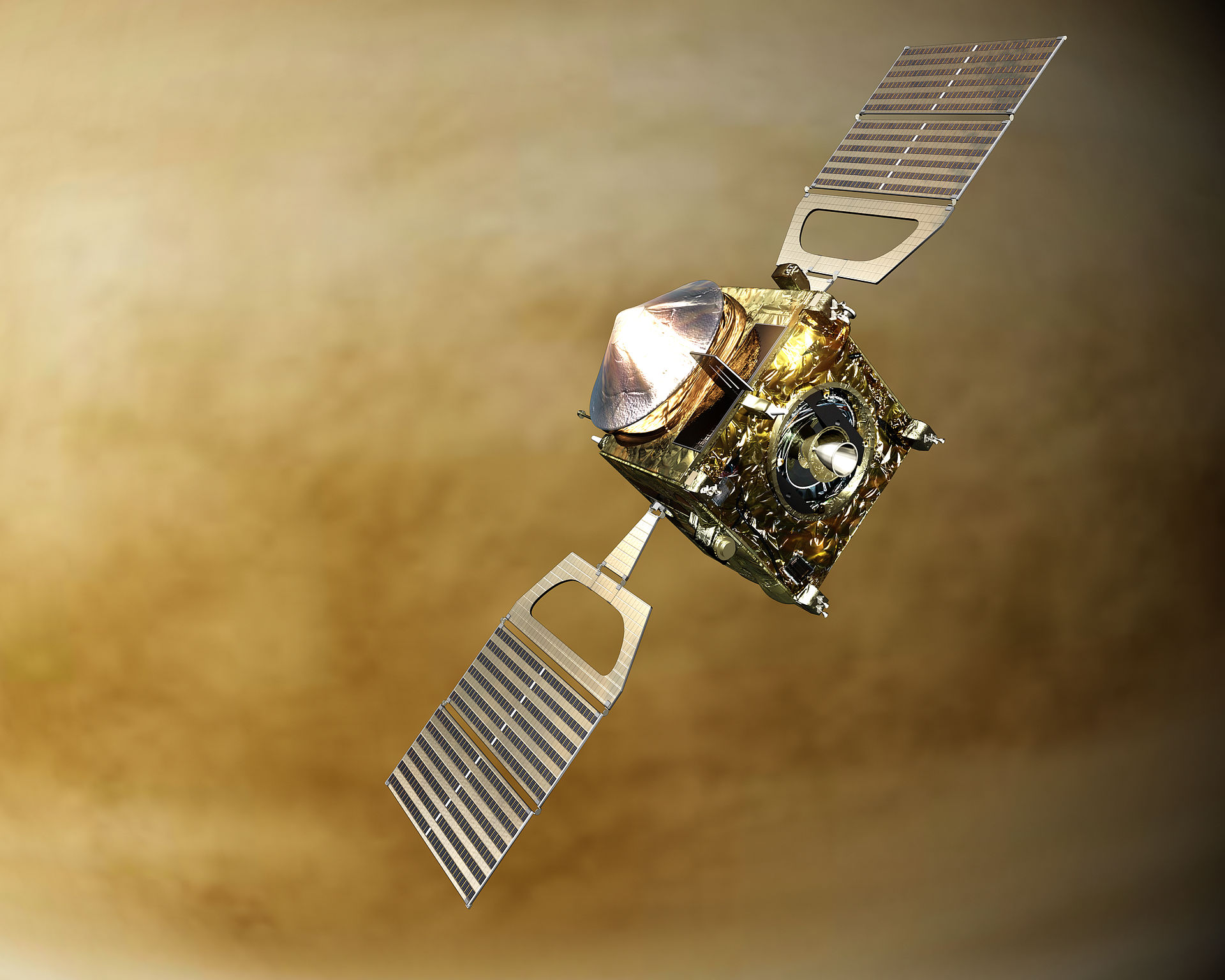

How do the three missions complement each other?

As DAVINCI plummets through the atmosphere, it will use its multi-band camera to take images of one of those interesting regions on the surface of Venus that we call tesserae. And what makes that extremely interesting is that this allows us to ground truth what VERITAS and EnVision can see from orbit. That means that in a way we can use the in-situ data from DAVINCI to calibrate the remote-sensing data that we are getting from VERITAS and EnVision.

Another thing that is complimentary about the missions is that both VERITAS and EnVision are radar mapping missions and that they are going to be mapping at different resolutions. This is going to give us some really interesting insights into the surface. In addition to that, the EnVision mission is going to include a subsurface radar which will give us an idea of what the structure of the subsurface is – maybe even as deep as tens of meters. People are very excited about that.

So it really is an advantage to have multiple spacecraft at the planet at the same time?

Absolutely! And there are at least two other missions that may also fly. There is an Indian radar mission that sounds very promising, although they have not released a lot of information. And there is also a long-term Russian mission called Venera-D, which is basically an upgraded version of their Vega probe. So we may have as many as five missions at Venus at the same time in a decade. That would be even more phenomenal.

And then you are going to be swamped by data.

It's better to be swamped by data than be swamped by nothing.

When will DAVINCI, VERITAS and EnVision arrive at Venus?

Venus is our closest neighbour – you wouldn't think that from reading the papers, you would think it's Mars – but you can get to Venus in less than six months. So I would be surprised if these missions aren't in Venus orbit or in the Venus atmosphere in the case of DAVINCI in 2032 at the latest.

Venus is our closest neighbour [...] and I would be surprised if these missions aren't in Venus orbit or in the Venus atmosphere in the case of DAVINCI in 2032 at the latest.

Is it like with Mars that you only have specific launch windows or can you go to Venus whenever you like?

No, it's the same as Mars, in the sense that you only have specific launch windows, but there are more of them as Venus takes less time to travel around the Sun. So Venus comes around more often than Mars does.

Do you already have specific papers in mind that you would like to write with the new data?

Oh yes! We all have papers in mind, but we'll have to see what the data gives us.

And will the focus still be the question of whether there was life on Venus at some point?

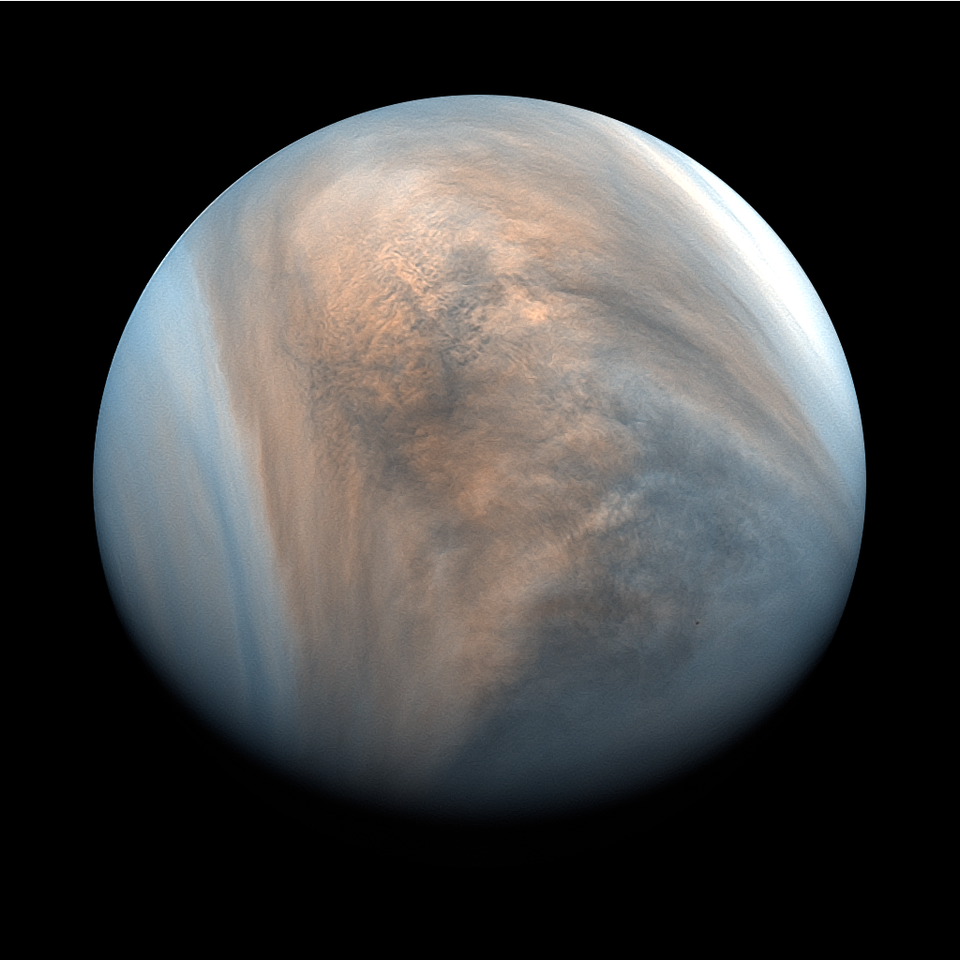

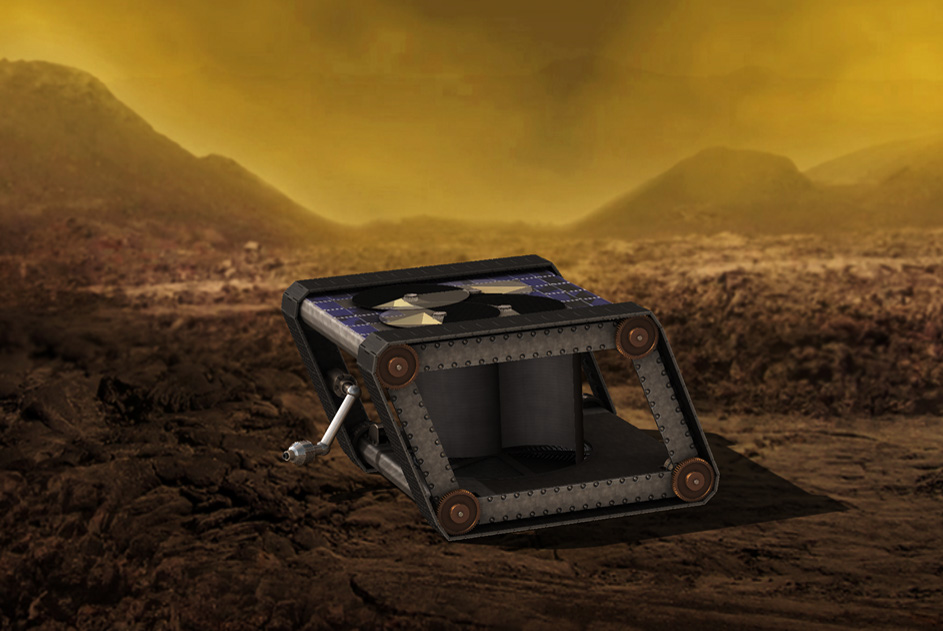

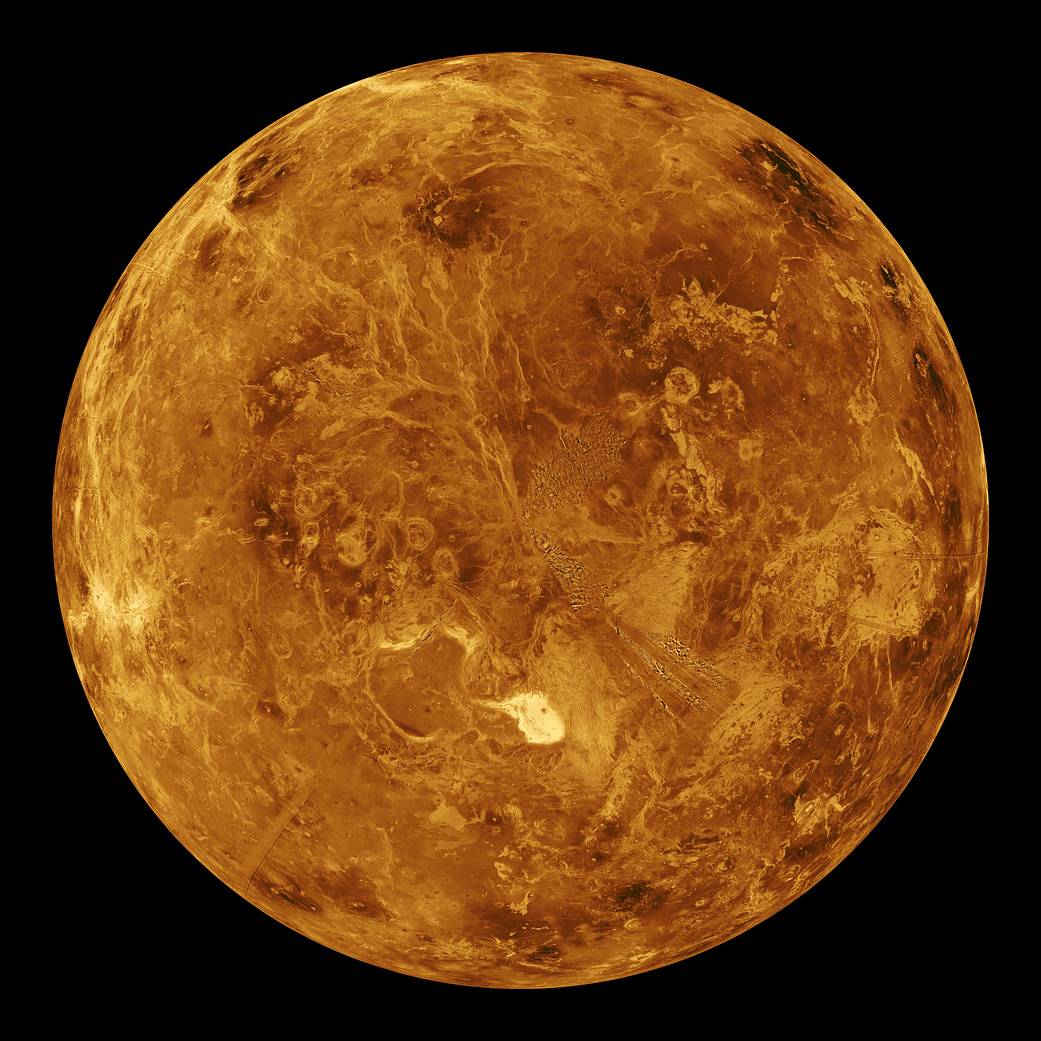

Yes, but it's not going to be the only focus. We have many other questions about Venus: What is the history of the surface? What are the tesserae and what are they telling us about the interior processes? And is volcanism still on-going on Venus? Another thing we would really like to do is to compare the data from the new radar missions to the data from the Magellan radar mission from the 1980s and see if we can make out any changes. We don't expect major changes, because it's not a geological timescale that we are talking about, but it's very likely that this is the first thing that people are going to be looking for. Another thing that the new missions are going to give us are high-resolution maps of the surface of Venus. And that means that we'll be able to pick much better landing spots for future Vega-type landers. Right now we only have fairly low-resolution data, so the safest place to put a lander is the volcanic plains, which are pretty flat. You have to be very careful when landing in areas with very steep slopes. You don't want your spacecraft to land and then topple over and crush your radar antenna. Because then you can't talk to anybody and tell them about all the wonderful things that you found.

Another thing that the new missions are going to give us are high-resolution maps of the surface of Venus. And that means that we'll be able to pick much better landing spots for future Vega-type landers.

So the overall goal still is to place a lander on the surface?

Absolutely! We have some measurements from the Vega and Venera probes that the Soviets sent, but we would like to use much better instrumentation and maybe sit down there a bit longer to really interrogate the surface in a way that we could only dream of 40 years ago. So I'm really hoping that the Venera-D mission will fly and that they will be able to fly upgraded instruments. Even if they land in the volcanic plains to be safe we're still going to learn tremendous amounts. But going down the road, once we have high-resolution radar images we'll be able to place these kinds of landers in places that we couldn't dream of today. It's the same for Mars, really. We have these extremely high-resolution images of Mars, and that's why we're able to land things in Gale Crater, in places that 30 years ago we could only dream about.

And will the new missions also be able to detect life on Venus?

I think that what we are going to learn about the possibility of an early temperate habitable period and the possibilities of life is really going to be coming from the DAVINCI probe and what it's going to tell us about the history of water on the planet. If it tells us that Venus had lots of water, but it was all lost four billion years ago, then that probably tells us that there wasn't much of any habitable period. But if it tells us something different, we'll know to start looking for hydrated minerals and the like on the surface. It's really going to help us focus our interest in a way.

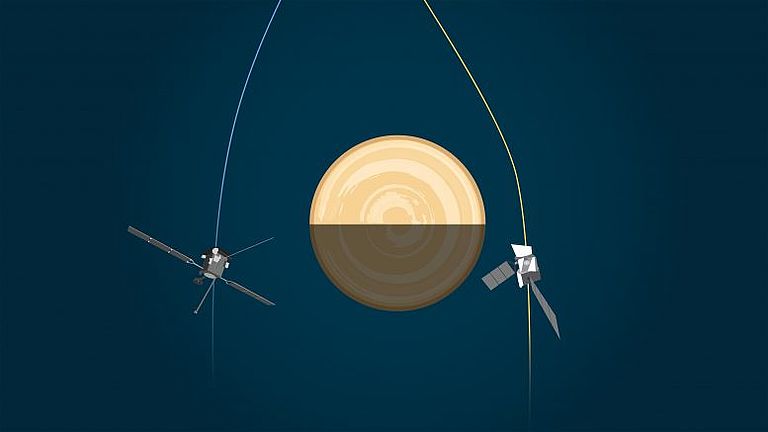

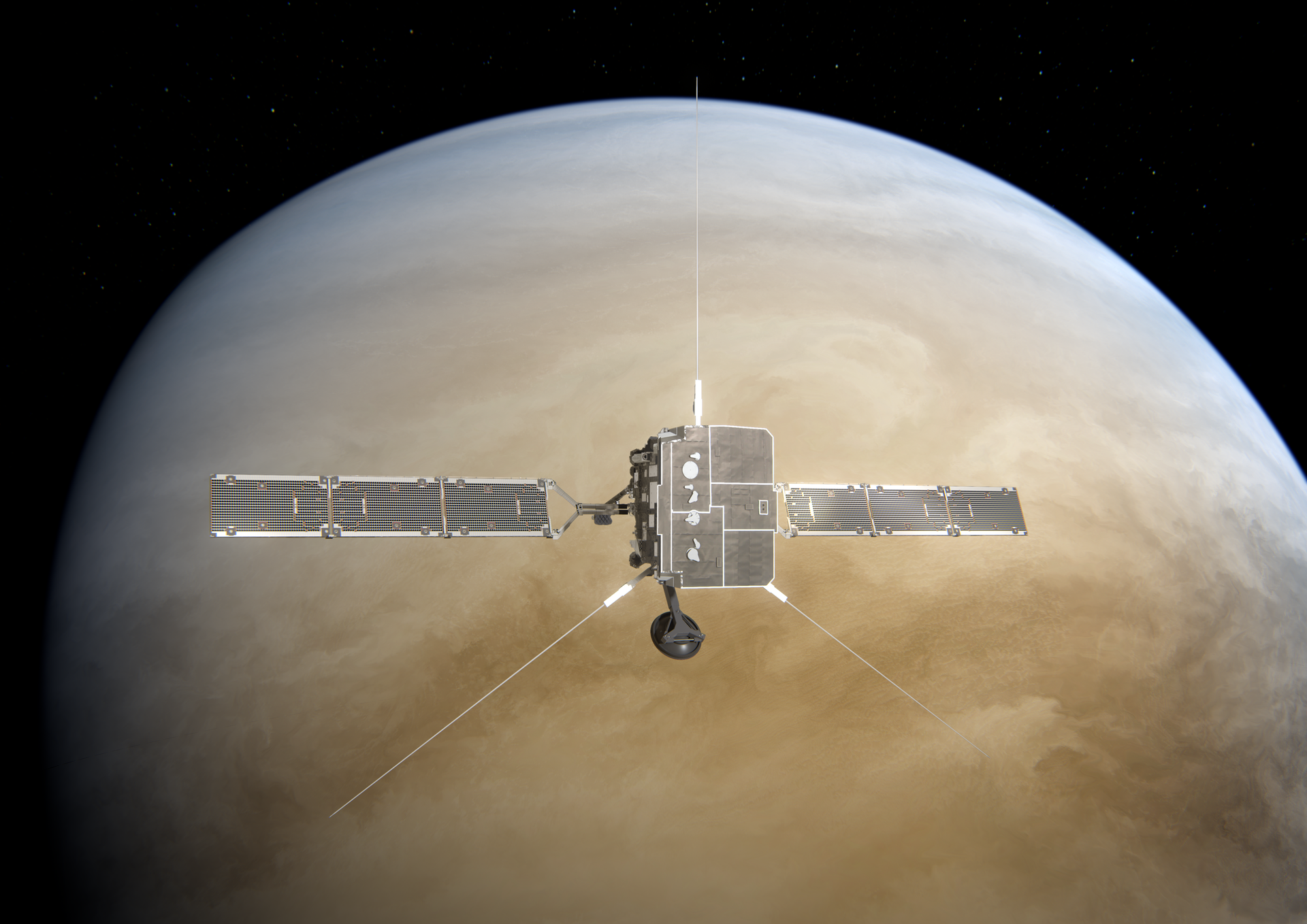

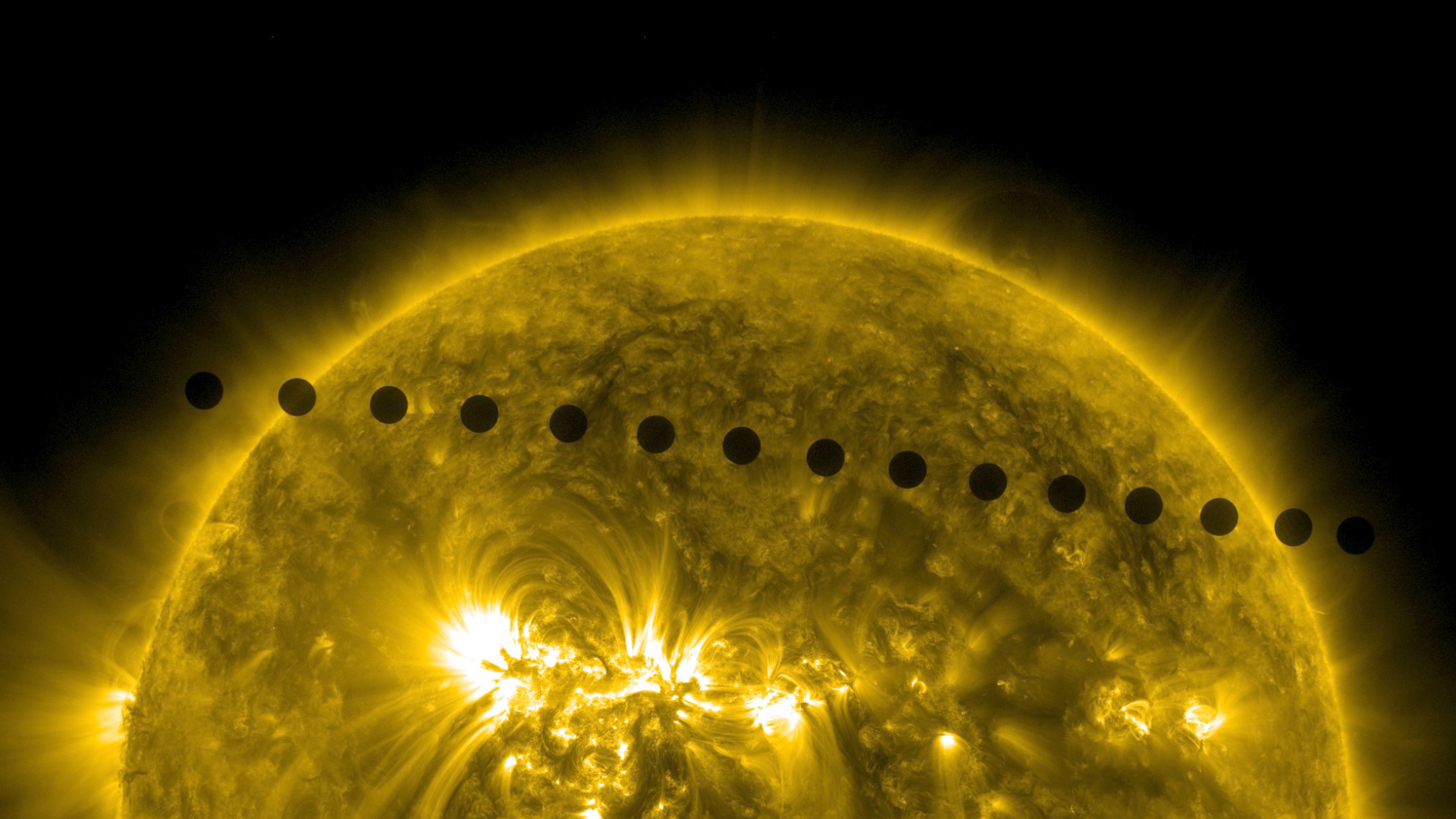

And what about the data that was collected by Solar Orbiter and BepiColombo on their recent flyby? Can you also use that?

I haven't seen any results from that yet. It takes a while to process the data. But hopefully they will give us some information. My feeling is that most of what they will be able to tell us will be related to the upper atmosphere, aspects of the ionosphere and the like. This is also very interesting of course, but it doesn't really relate to questions of habitability.

So you will have to wait.

Yes, I will have to wait. But in America we don't have restrictions on how long you can work. So if I'm still feeling good and going strong and my brain is still working when the data finally becomes available, I would be delighted to continue my work with it. It'll be a very exciting time for planetary science in general and especially for people interested in Venus.

Dr Michael Joseph Way from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies is convinced that the three new Venus missions DAVINCI, VERITAS and EnVision will contribute enormously to expanding knowledge about our nearest neighbouring planet. He himself already has a few papers in mind that he would like to write using the new data.