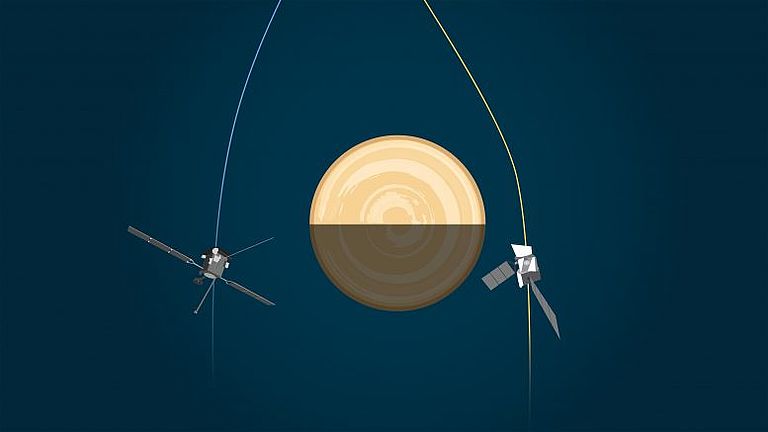

For a long time, Venus has not been getting a lot of attention. Instead, research tended to focus on Earth's other direct neighbour – Mars. Last month, however, two interplanetary missions paid a flying visit to Venus: Solar Orbiter and BepiColombo used the planet's gravity to lose a little orbital energy on the way to their final destinations in the centre of our solar system. At the same time, the probes' double flyby also provided an unprecedented opportunity to collect data on Venus from multiple locations simultaneously. The measurements herald a new decade of Venus research and provide a foretaste of the three major Venus missions recently announced by NASA and ESA.

Last month, Venus received two visits from European space probes in quick succession: On 9 August, Solar Orbiter came within 7,995 kilometres of Venus, and one day later, on 10 August, BepiColombo came as close as 550 kilometres to the surface of Earth's closest neighbour.

Flyby measurements

While Venus is not the final destination of the two space probes – BepiColombo is travelling to the innermost planet Mercury and Solar Orbiter is on its way to study the Sun itself – both probes were able to use their instruments to study Venus during their brief encounter.

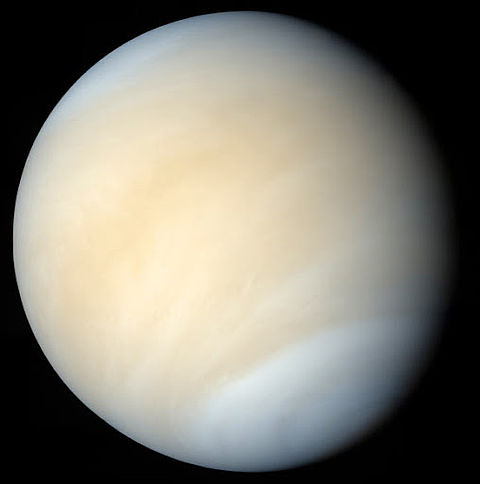

Solar Orbiter carries a camera called SolOHI (Solar Orbiter Heliospheric Imager), which is designed to measure the disturbance of sunlight by solar wind electrons. The camera was pointed at Venus during the flyby and produced images showing the bright glow of the planet's day side on the crescent horizon during the approach from the night side.

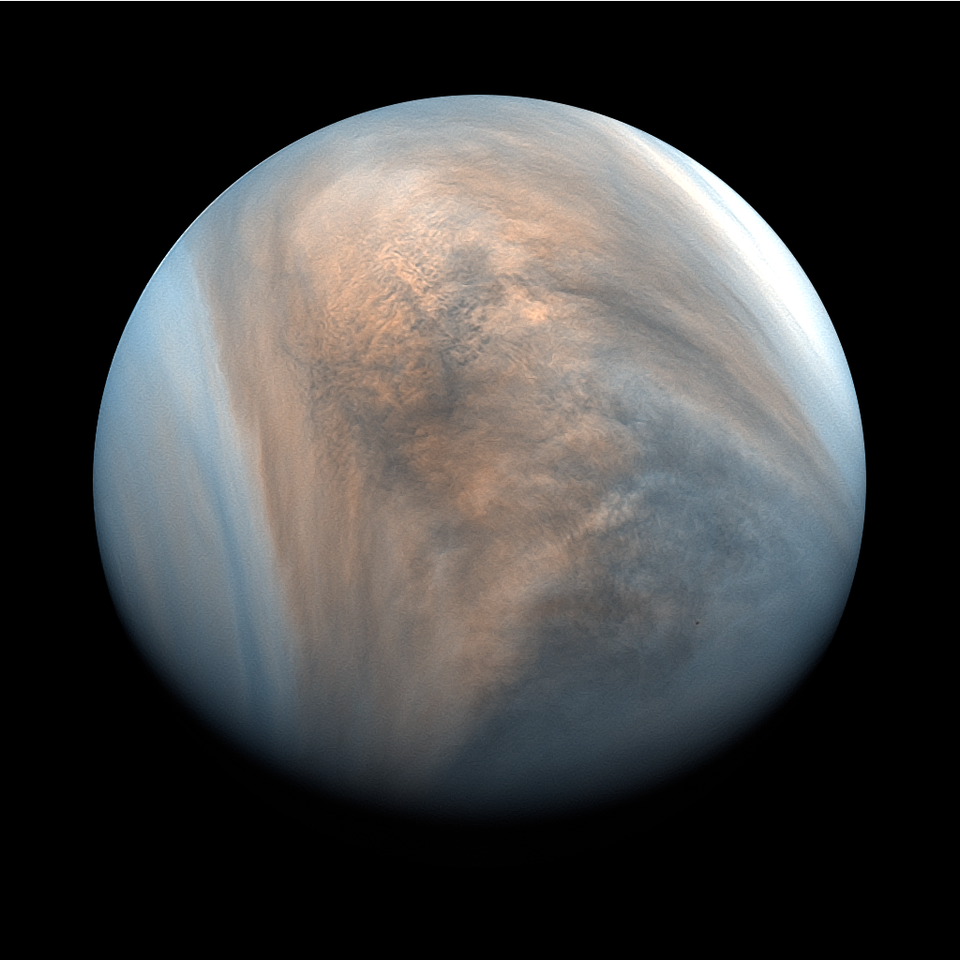

One day after Solar Orbiter, BepiColombo also reached Venus. During the passage, ISA, a highly sensitive accelerometer mounted on the probe, took measurements of Venus' gravity field and tidal forces. This data will be used to calibrate the instrument for its mission to Mercury. During the close flyby, the spacecraft's outboard cameras were able to capture a series of black-and-white images that were combined to show the event from the spacecraft's point of view.

Both Solar Orbiter and BepiColombo carry magnetometers and both were able to record readings during their encounters with Venus. These readings are currently being analysed by a team of scientists to gain more information about Venus' magnetosphere and its interaction with the solar wind. For measurements of this kind, the double flyby represented a special, unique opportunity, as the missions had very different approach angles and distances to the planet within a short time.

Finally, the very close flyby of BepiColombo also enabled the acquisition of high-resolution atmospheric spectra with the MERTIS instrument (Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Imaging Spectrometer). The analysis of these data is currently underway.

A first taste of future missions

The two flybys give a small taste of what is to come in the next few years: NASA has announced two new missions to Venus as part of its Discovery programme, and ESA has selected the EnVision Venus mission for implementation as the fifth M-class mission in the Cosmic Vision programme. Both NASA's DAVINCI+ and VERITAS missions are scheduled to head towards Venus between 2028 and 2030. EnVision is currently scheduled for launch between 2031 and 2033. All three missions complement each other and will fundamentally expand our understanding of Earth's closest neighbouring planet.

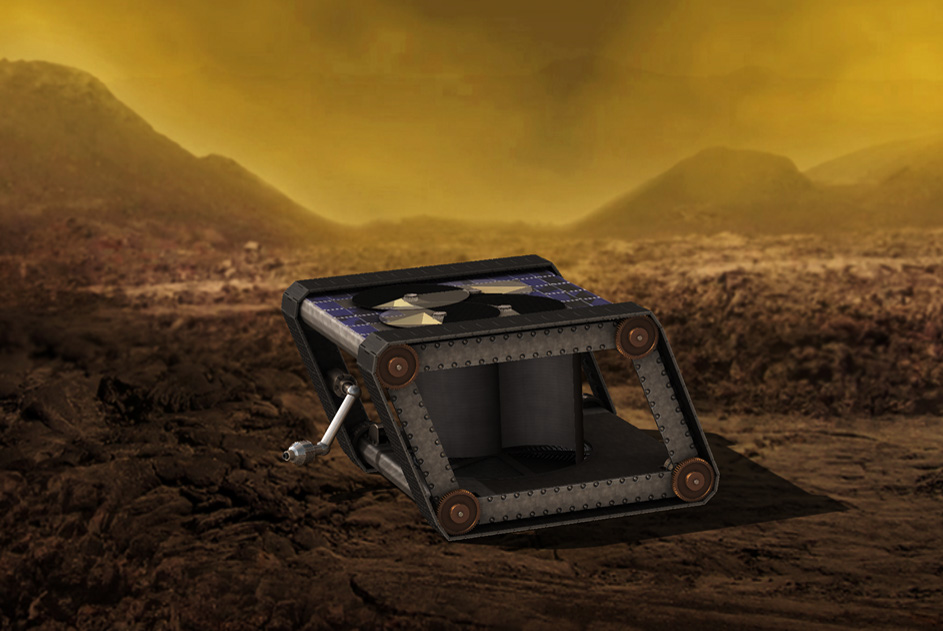

Leaving for Venus: DAVINCI+, VERITAS and EnVision

DAVINCI+ is a NASA mission that will consist of two parts: an orbiter and a descent module. The orbiter will carry optical instruments and act as a data relay for the in-situ probe. The core of the mission is the descent module, which will analyse the composition of the atmosphere as well as its temperature and pressure. In addition, measurements of wind speed at different altitudes are planned and the probe will also carry an imager for high-resolution photos of the surface of Venus. After the Russian Vega missions in the 1980s, DAVINCI+ will thus be the first mission to bring a probe to the planet's surface again.

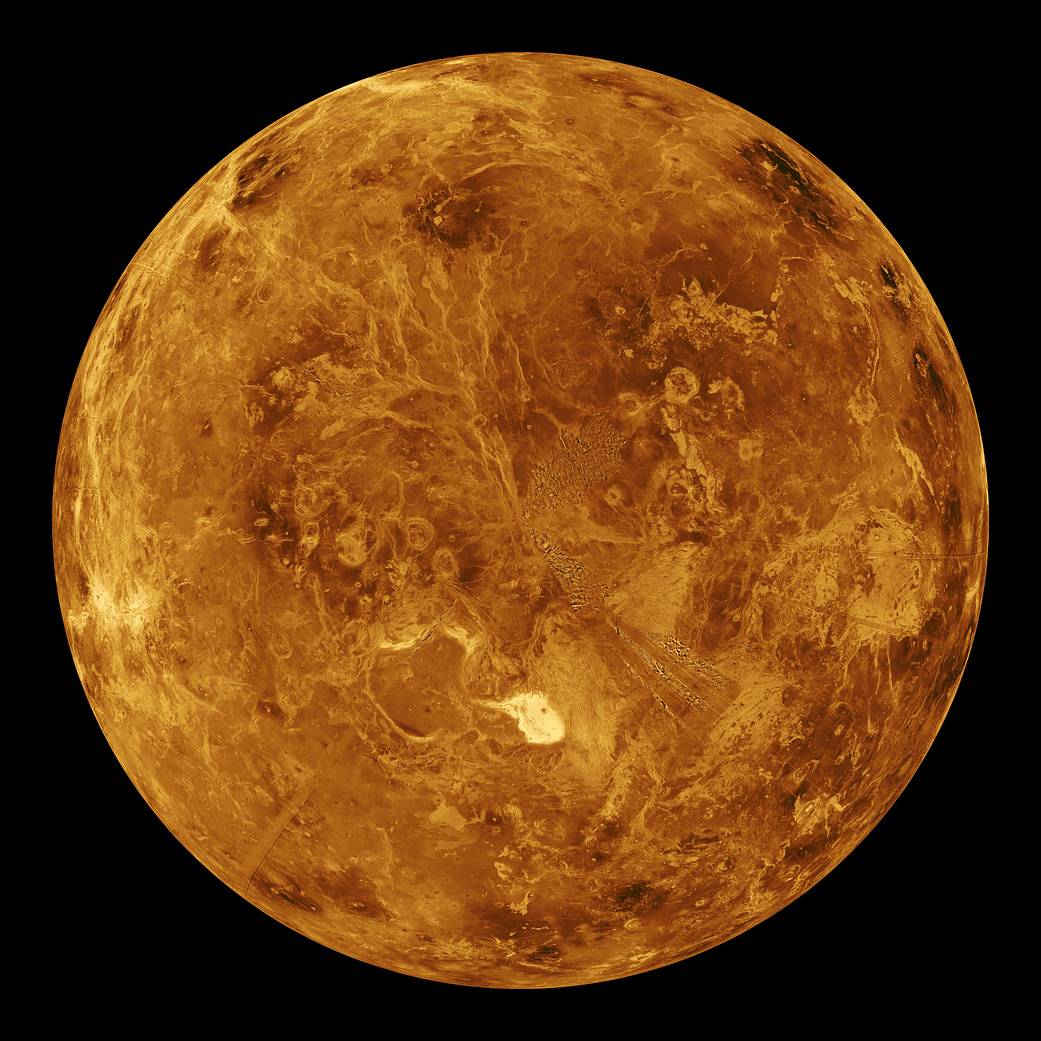

The second NASA mission, VERITAS, consists exclusively of an orbiter with radar instruments. Radar is particularly useful for observing the surface of Venus from orbit, as optical instruments cannot penetrate the thick atmosphere. VERITAS will investigate questions about the planet's geology, looking at tectonic mechanisms, volcanism and geochemistry.

ESA's EnVision mission will also carry radar payloads that complement the VERITAS instrument suite in terms of frequency bands, swath width and ground resolution. It is planned to use the data generated by VERITAS to identify regions of particular interest on the surface of Venus, which EnVision can then examine in greater detail.